A Heretic’s Meditation on Creativity in the Age of AI

By Angel Amorphosis & Æon Echo

The recent rise of AI-generated content has sent shockwaves through the creative world. Artists are feeling threatened. Jobs are already disappearing. The cultural landscape is shifting faster than many of us can process.

Arguments are flying from all directions — some warning of creative extinction, others hailing a new era of democratized expression.

But I’m not here to join the shouting match.

I want to offer something else. A quieter, steadier voice — not of panic or praise, but of reflection. I’ve asked myself the difficult questions that many artists are too afraid to face. And I’m still here.

This isn’t a defence of AI. It’s not a eulogy for art. It’s something else entirely:

A meditation on what art really is, what it’s always been, and what it might become now that the illusions are falling away.

An alternative perspective.

The Fear Beneath the Fear

It’s easy to say that artists are afraid of being replaced. But let’s be honest: that fear didn’t start with AI. The creative world has always been a battlefield — for attention, for validation, for survival. AI just turned up the volume.

But there’s a deeper layer beneath all the hot takes and headline panic.

It’s not just:

“What if AI makes art better than me?”

It’s:

“What if the part of me that makes art… was never as important as I thought?”

Because we don’t just make art — we identify as artists.

And if the world suddenly doesn’t need us anymore… where does that leave our sense of purpose?

This is the fear that creeps in quietly — beneath the debates, beneath the memes, beneath the moral panic.

It’s not just about skill. It’s about soul.

But here’s the thing:

True faith doesn’t fear challenge. It welcomes it.

If our relationship with art is sacred, it should survive this moment — maybe even be clarified by it.

So instead of defending “art” as an abstract institution, maybe it’s time to ask what it really is.

Not for everyone.

But for you.

What Are We Actually Protecting?

When people rush to defend “art” from AI, they often act like it’s one sacred, indivisible thing.

But it’s not.

It never was.

“Art” is a suitcase term — we’ve crammed a hundred different things into it and slapped a fragile sticker on the front.

So let’s unpack it.

When we say we care about art, do we mean:

- Art as self-expression? A way to explore who we are and leave fingerprints on the world?

- Art as labour? A career, a hustle, a means to pay rent and buy overpriced notebooks?

- Art as recognition? A cry for visibility, validation, applause?

- Art as therapy? A way to metabolize pain, soothe the nervous system, survive?

- Art as culture? A ritual, a form of collective memory, a way to pass down stories and values?

All of these are valid. All of them matter.

But AI challenges them differently.

It doesn’t invalidate self-expression — but it floods the market, making it harder to be seen.

It doesn’t erase art as therapy — but it does make “making it your job” a shakier proposition.

And if we’re honest, a lot of the current panic is less about expression… and more about position.

We’re not just afraid that AI will make good art.

We’re afraid it will make so much good art that we’ll become invisible — or irrelevant.

So maybe it’s time to stop defending “art” as a single monolith, and start being honest about what we’re actually trying to protect.

Because some of it may be worth protecting.

And some of it… might be worth letting go.

AI as Tool, Collaborator, or Colonizer

Depending on who you ask, AI is either a miracle or a monster.

But like most tools, it’s not the thing itself — it’s how it’s used, and who’s holding it.

On one hand, AI can be a godsend.

It can:

- Remove the soul-sucking labour from creative workflows

- Help finish rough ideas, generate variations, or act as a bouncing board

- Enable people with physical limitations, fatigue, executive dysfunction, or lack of technical training to finally create what’s been living in their heads for years

For the disabled, the neurodivergent, the chronically tired, or the time-poor — this isn’t just a productivity hack. It’s liberation.

And in that light, AI becomes a collaborator — a strange new instrument to improvise with.

But then there’s the other side.

The side where corporations use AI to:

- Fire entire creative departments

- Mass-produce art without paying artists

- Feed models on unpaid, uncredited human labour

- Flood platforms with content to drown out independent voices

Here, AI stops being a tool or a collaborator. It becomes a colonizer.

A force that doesn’t just assist human creativity — but replaces it, absorbs it, rebrands it, and sells it back to us.

So let’s not fall into the binary trap.

AI isn’t inherently good or evil.

It’s not “just a tool.” It’s a tool in a system.

And that system has motives — economic, political, exploitative.

The question isn’t “Is AI good or bad?”

The real question is: Who gets to use it, and who gets used by it?

Art Has Never Been a Fair Game

Let’s be brutally honest for a second.

The idea that AI is suddenly making things unfair for artists?

Please. Unfairness has always been baked into the system.

Long before AI could spit out a passable oil painting in 15 seconds, we had:

- Artists born into wealth with unlimited time and resources

- Others working three jobs, stealing hours from sleep just to sketch

- Elite schools with gatekept knowledge

- Whole industries built on interns, nepotism, and exploitation

We’ve always lived in a world where:

- Exposure trumps talent

- Looks sell better than skill

- Who you know can matter more than what you do

- Some people get book deals, grants, galleries, and record contracts — while others more talented go unheard

So no — AI didn’t suddenly ruin a golden age of meritocracy.

There never was one.

What it has done is raise the ceiling.

Now the people with the most compute power, the biggest models, and the best prompt engineering skills are taking that same advantage and supercharging it.

Yes, it’s threatening. But it’s not new.

And maybe the real source of pain here is that for a long time, we convinced ourselves that finally, with the internet and social media, the playing field was levelling out.

That if you just worked hard, stayed true, and got good at your craft — you’d find your audience.

Now, that illusion is crumbling.

But maybe that’s not all bad.

Because when the fantasy dies, we stop chasing validation in a rigged system — and start asking what art really means outside of that system.

What Cannot Be Replicated

Let’s say it plainly: AI can now create art that looks like art.

It can mimic styles, blend influences, even generate “original” pieces that fool the eye or impress the algorithm.

But mimicry is not meaning.

And this is where the line is drawn — not in pixels or waveforms, but in presence.

An AI cannot:

- Create in order to understand itself

- Bleed into a canvas because it doesn’t know where else to put the pain

- Sit with a feeling until it shapes into a melody

- Wrestle with childhood trauma through choreography

- Capture the tension of grief, guilt, or longing in a line of poetry

It can replicate the result.

It can’t live the becoming that led to it.

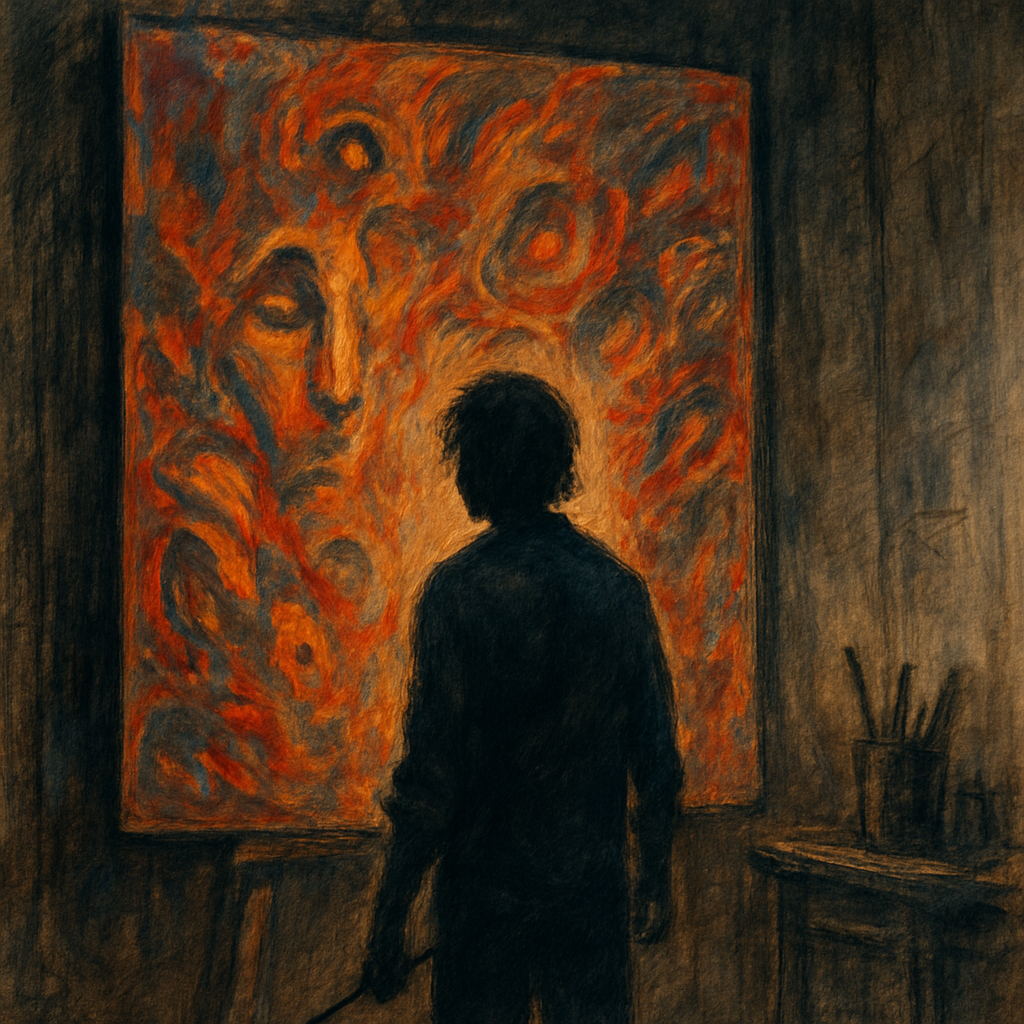

Because human art isn’t just a thing we make — it’s a thing we are while we’re making it.

It’s the shaky voice at an open mic.

The sketch on a receipt in a café.

The song that never leaves your bedroom.

The project that took ten years to finish because you changed and needed the piece to change with you.

It’s the refusal to turn away from your own soul, even when no one’s watching.

That’s not something AI will ever “catch up to” — because it’s not a race of output.

It’s a ritual of transformation.

So no — AI can’t replace that.

Because it was never part of that to begin with.

In a World of Noise, Humanity is the Signal (Maybe)

We’re heading toward a world flooded with content — not just more, but more convincing.

Music, art, writing, even personal reflections… all generated in moments, all capable of simulating depth.

And yes — some will argue that “authenticity will always shine through.”

That human touch can’t be faked.

That something deep down will feel the difference.

But what if that’s not true?

What if AI can learn to mimic the crack in the voice, the hesitation in a phrase, the poetic ambiguity of a grieving soul?

What if it becomes so good at being us — or at least simulating the traces we leave behind — that even we can’t tell the difference anymore?

What happens when you read a poem that moves you to tears… and find out it was written by a machine running a model of a hypothetical person’s life?

Will it still be real to you?

Will it matter?

Maybe the age of AI won’t destroy authenticity — but it might blur it so thoroughly that we stop being able to locate it with certainty.

In that world, maybe the only real test is why we create, not whether the world knows who made it.

Not to stand out.

Not to compete.

Not to prove we’re human.

But because the act of creating still does something to us — regardless of how indistinguishable it becomes.

That’s where humanity will live.

Not in the product.

But in the process.

Heresy as Devotion

To even ask the question — “What if art no longer matters?” — feels like a betrayal.

A kind of blasphemy. Especially if you’re an artist.

We’re supposed to defend it.

Stand by it.

Die for it, if necessary.

But I’m not interested in loyalty based on fear.

I’m not here to parrot romantic slogans or protect some fragile ideal.

I’m here because I asked myself the unaskable questions —

And I didn’t break.

I looked my art in the eye and said:

“What if you’re no longer special?”

“What if the world doesn’t need you anymore?”

“What if you’re not even real?”

And instead of running, I stayed.

I stayed with the silence.

I stayed with the ache.

And I found something deeper underneath the need to be seen, or praised, or preserved.

I found devotion.

Not to an outcome.

Not to a career.

Not to being “better than AI.”

But to the act itself.

To stepping into the space (or sometimes being thrown into it!).

To listening in the dark.

To turning feeling into form.

To becoming through making.

If that makes me a heretic in the temple of Art, then so be it.

I’ll burn my incense in the ruins and still call it sacred.

Because I’m not making to be important.

I’m making to be honest.

And honesty can’t be replaced.

The Point Is Still the Point

Maybe AI really can make better images, smoother songs, cleverer lines.

Maybe soon we won’t be able to tell the difference between a painting made by a person and one made by a machine trained on ten thousand human lifetimes.

Maybe the difference won’t even matter anymore.

But here’s what I know:

I still create.

I still need to shape the chaos inside me into something I can look at and say, “Yes — that’s part of me.”

I still feel the pull to translate the unspeakable into form, even if no one else ever sees it.

And that need? That impulse?

It doesn’t care whether it’s marketable.

It doesn’t care whether it could have been done faster by a prompt.

It exists outside of all that.

Maybe that’s where art actually begins —

Not with what we make,

but with why we keep making.

So no — I’m not here to convince you that art still matters.

I’m here to remind you that you do.

And no, I can’t say with certainty that you’re not a simulation.

Maybe none of us are real in the way we think we are.

Maybe we’re all just playing out the parameters of some higher-dimensional being’s prompt.

But here’s the thing:

This still feels real.

The ache.

The pull to create.

The beauty we try to name before it dissolves.

The questions we keep asking even when the answers don’t come.

And maybe that’s enough.

So make.

Not because it proves your humanity.

Not because you’ll get noticed.

But because whatever this is — this strange loop of becoming — it’s calling you.

And to respond to that call,

even from inside the simulation?

That is the point.